How Art Is Made #1: The Intaglio Etching

These days, you hear a lot about “cloning.” For instance, Dolly, a Finnish Dorset sheep, was born on July 5, 2006 at the Roslin Institute in Scotland via a process known as nuclear transfer whereby a life emerged simply from a somatic cell in a mammary gland. Humanity has long been fascinated by exact replicas. Along the Silk Route, as the human population increased, there was a similar yearning for the ability to “reproduce” goods and services from fabrics and ceramics to foodstuffs and weaponry on a mass scale.

One such case is that of the Gutenberg Press of 1450 which allowed for over 3,500 pages to be duplicated each day as compared to a previous process of rubbing or brushing by hand at a rate of less than 40 pages daily. The printing press, more broadly, is considered one of the most important advancements of the 2nd millenia, because it expanded literacy rates globally. As humanity’s drive to reproduce more and more, faster and faster accelerated, today, our modern copiers, such as a XEROX machine, can make multiple facsimiles instantaneously – up to 115,200 reproductions in a single, 8-hour work day.

But, where did this technology of making copies on metal arise from?

Today, I introduce you to the technique known as etching, and one, likely apocryphal, account of its origins.

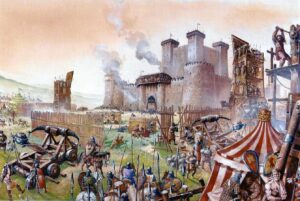

Imagine you are in a medieval, military encampment – laying siege to a town. To add color to the story, let’s say that it’s York in northeastern England. As soldiers, we are sitting around a campfire exchanging exploits of our past heroics. As the vanguard, we wear armor. It helps our skin not get slashed by these new fangled metal swords which otherwise slice through us like butter. But, with armor on, a new problem arose. It is now much harder to ascertain the identity of fallen bodies on the battlefield. Now, this might not matter to us lowly knights. But, if you are Guinevere, you want to know if the fallen armor-clad warrior is your husband, King Arthur, or your lover, Lancelot. So, what did we do? We took our sword and scratched an “A” for Arthur and an “L” for Lancelot. This is the technique called engraving. It was good but not great. It didn’t allow for subtle designs such as our florid family crests. So, back to our campfire!

One of us gets up to pee in the woods after a few carafes of ale. He stumbles and kicks a giant cauldron of acid which we were intending to trebuchet over the castle ramparts at sunrise. The acid spills over and onto our pile of armor, chest plates, spears, shields and battle axes. We all mock him mercilessly and sling epithets at him about his mother. But, we also notice something very, very unexpected. Everywhere that the acid fell on and touched our armor, the acid eats a hole through the metal. Uh-oh! In seconds, the metal is literally not there anymore – with one glaring exception. Everywhere that we had spilled bacon grease on our armor while cooking, the acid wasn’t able to gobble up the metal. Nitric and ferric chloric acid can eat through zinc and copper respectively – but, evidently, not through organic compounds, such as bacon grease. This is a Eureka moment!

Engineers and artists took this observation back into the lab and studio and produced marvelous results.

Now, let’s pretend you are Rembrandt (1606-1669) or Goya (1746-1828). You take a brush. You dip it into a bacon-grease resist – something like gum arabic. You make elegant designs on a plate of metal with that brush. You then bathe your metal plate in a tub of acid. Everywhere you have touched the metal with bacon grease, the acid has no effect. But, everywhere that the metal plate is not covered by bacon grease, the acid burrows a little pore or trough into the surface of the metal. You repeat the process and expose the metal plate to longer acid baths, if, by any chance, you want areas of your design to be darker (for example, the hair in Rembrandt’s self portrait). Essentially, the longer the metal plate is in the acid bath the deeper the pore becomes and the more ink it will eventually hold that will be transferred to the piece of paper.

So, now, once your design on your metal plate is finished to your satisfaction, we turn to our final step, the actual printing! We take our metal plate and lay it on a printing press; we cover it with a damp piece of paper; we cover both with blankets; we roll it all through a high-pressure vice. The combination of the moisture and pressure draws the ink out of the pores or troughs and onto the paper. Voila!

Now, you should have some better understanding as to how etchings are made and where the technology arose from.

I strongly encourage you to go see Goya’s “Disasters of War.” They are some of the most harrowing images ever made about the calamities of human conflict. Revisiting them this week for me was particularly poignant in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the leveling of Mauripol.

As for myself, my own series of intaglio etchings, “What Falls Away” of toy figurines, are in the permanent collections of the Fogg Art Museum, the Allen Memorial Art Museum and the New York Public Library. You can see some of them at my Instagram: have_a_nate_day

Until we connect next week, delight in the world; exchange love with those around you; and, above all, awaken more and more to your own awesomeness.